While the major motivation for our maiden voyage to northern New Mexico in 1992 was to see what gave Georgia O’Keeffe all those ideas for her “abstract art” we also, as we remember it, expected to experience at least a little bit of its namesake country to the south – although never having visited there we had no idea what. However as Shakespeare has Juliet ask, “what’s in a name?” – by which the play-write meant that a name is just a label and doesn't define the true nature of something.

So how “Mexican” was it? Well we bought some blankets from a street vendor that were made there. And checked out other stuff that we thought might be representative of that country such as Virgin of Guadalupe, Frieda Kahlo and Day of the Dead collectables. But Santa Fe’s earth-colored buildings looked more North African (where we also have not been) than south of the border. And neither the Native American pottery beautifully decorated with intricate geometric designs nor the small paintings on wood created by Spanish artists charmingly depicting saints and other Catholic iconography that we saw seemed to have a place in our Mexicano expectations.

We would later come to learn that New Mexico was a part of Mexico from just 1821 to 1848 – barely a tick on its history timeline. And was given that name by Spain in 1598, probably after an Aztec legend of a distant northern land called “Yancuic Méxihco.” The country of Mexico named itself that when it won its independence from Spain in 1821, having been dubbed “New Spain” by its conquerors 300 years earlier. During that time each colony developed its own identity and culture in spite of being geographically adjacent.

Here’s how.

The Americas were settled around 12,000 years ago by PaleoIndians – nomadic hunter-gatherer-foragers who spread over an extensive geographical area, resulting in wide regional variations in lifestyles. Next came “Archaics” – also hunters, gatherers, and foragers who, because large herd animals were becoming less available, switched to smaller animals and a wider assortment of wild plants. This in turn led to the “triumvirate of Puebloan traits” – agriculture, sedentariness, and village-scale organization. Some sedentary places turned out to be better than others.

“Southern cultures became agrarian-based and took advantage of the virtually year-round growing season in their part of the world ... [allowing them] (A) to support larger populations, and (B) to enable the rise of privileged classes of individuals who had the time to acquire knowledge and produce more advanced technologies in construction, astronomy, medicine, etc [much like] early Middle Eastern cultures.” (William Osborne, Quora.com)

North of the Rio Grande River, however, seasonal climates limited agricultural production. Plus a more abundant supply of large mammals for hunting made agriculture less important. These northerners had much lower populations than the tribes in Mexico, Central America, and South America.

Enter the 16th century Spanish.

In expanding its empire Spain had three equally important goals – expansion of Catholicism to the exclusion of other religious traditions, material wealth, and enhancement of the status of both the individual conquerers and the crown – “God, gold and glory.”

That meant “exploring new lands, claiming them for the Spanish crown through expeditions led by conquistadors, establishing settlements, exploiting the land's resources like gold and silver, forcing indigenous populations into labor systems like the encomienda, and converting them to Catholicism, all while establishing a strict social hierarchy with the Spanish elite at the top.” (Google AI)

South of the Rio Grande the Spanish found silver (which became a major source of income for the crown,) gold, mercury (used in silver refining,) corn, beans, and fertile land for their favored crops of wheat and sugar cane. Up north – not much exploitable resources other than the labor of the indigenous people.

Mesoamerica had advanced cultures like the Maya and Aztec with highly developed urban centers, complex writing systems, and intricate religious practices; a diverse array of other tribes and a history of large-scale uprisings. New Mexico’s Natives were primarily composed of independent Pueblo tribes divided by language, religion, and family connections who interacted only for trade – plus additional nomadic groups like the Apache and Comanche. Less complex and more localized.

Modern day New Mexico culture stems from a stronger blend of indigenous Pueblo traditions and a greater emphasis on Native American heritage within the state's identity, resulting in uniquely distinctive architecture, art forms, and cuisine that differ from those found in present-day Mexico. NM also has its own unique dialect of Spanish – a more specific mix of 17th century Spanish and Native American influences compared to the broader blend seen in Mexico, which incorporates more Mesoamerican indigenous elements – and being a trade center kept up with changes in the vernacular.

It was the unique architecture and works of art in the museums, shops and galleries that took our breath away on that first visit. And still does.

New Mexico’s buildings are a blend of Spanish, Native American, and American influences, while Mexican architecture is influenced by Spanish colonial styles.

The original 17th century NM colonists were familiar with the use of adobe as a building material as a result of the North African Moors control of their country from 711 AD until 1492 AD. The Pueblo Indians already lived in housing featuring adobe walls, flat roofs, and kiva fireplaces, which the colonists readily adopted and adapted to their needs. Over time the style was enhanced to reflect New Mexico's U.S. territorial history with pitched roofs, stucco exteriors, and symmetrical facades. And later a modest Spanish Colonial Revival with red tile roofs, arched doorways, and ornate detailing. In our hometown this was codified as “Santa Fe Style” in 1912. The resulting architecture is unique and has been named one of the “Dozen Distinctive Destinations in America” by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The Spanish cemented their power over Mexico by imposing their architecture on the colonized Mesoamericans. Spanish architects brought Gothic, Islamic, and Renaissance traditions to the New World – beginning with forts and churches, then expanding into housing and trade buildings as populations grew. The decline of native populations in villages and Pueblos encouraged the consolidation of power in urban centers. However indigenous artists and craftsmen still added their own touches, e.g. carving church reliefs in native styles, known as “tequitqui sculpture.” Likewise the central plazas and orderly grids of Aztec cities were incorporated into the new Spanish construction work and soon spread to other colonies and Spain itself.

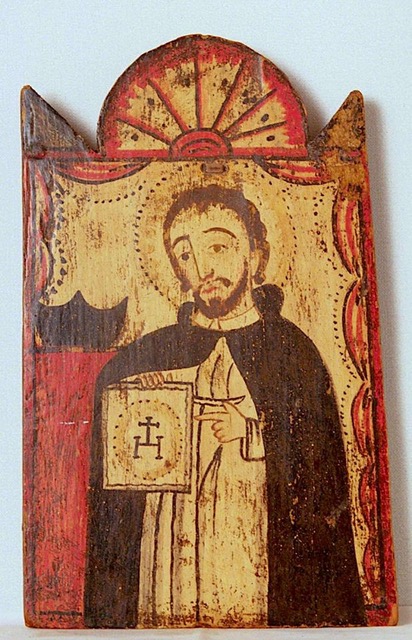

In the world of “fine art” the differences were even more striking. 18th century art in Mexico was characterized by splendor, while in remote New Mexico artistic output was considerably more modest. South of the border saw the spread of portraits, room screens, devotional imagery and “Casta paintings” (depictions of racially mixed families popular with colonial elite) plus murals on the walls of sacristies, choirs, and university halls – all created by classically trained artists using then state-of-the-art materials. Up north self-taught artists used local natural materials to create “retablos” of Christian saints and holy figures on hand-hewn cottonwood surfaces as shown above to decorate their otherwise plain adobe chapels. Today paintings created in the exact same manner by descendants of these “santeros” can be found in museums and galleries and on the walls of folk art collectors around the world. Including ours.

According to the latest census, around 50.1% of New Mexico's population identifies as Hispanic or Latino. A significant portion would likely classify themselves as Mexican, however the survey asked for ethnicity rather than ancestry. The Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Catholic shrine in Santa Fe (late 1700s – early 1800s) is the oldest church in the United States dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe indicating that, as an object of worship in New Mexico, the VoG may have preceded Mexico’s 1821 country-hood and its takeover of the colony. Frida Kahlo came on the world art scene in the late 1930s. And exploded on the pop culture scene in the 2002 after Salma Hayek's biographical film of the painter – becoming an icon for the feminist and then LGBT movements and appearing, like the Guadalupe on tee shirts, votive candles, tattoos, lowrider cars etc. in her own “church of Frida.” In researching this we realized that we probably misremembered her omnipresence in 1992. She most likely showed up here around 2005 or so. Thirty-five years of Santa Fe-ing can become a blur.

Suffice it to say however that Hispanic culture comprises a major part of New Mexico’s customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements. And that its people’s three most recognizable Mexican icons – the Virgin of Guadalupe, Frida Kahlo and Day of the Dead skeletons – are pretty much ev-e-ry-where out here. Together with intricate Native American pottery, whimsically devotional paintings of Spanish Catholic saints, lots of Georgia O’Keeffe & friends, and mucho, mucho más.

Yancuic Méxihco. “What’s in a name?”

More than we would of thought.

So New England readers may ask, “why didn’t something like that happen here?”

The Spanish colonization strategy encouraged marrying and procreating with the Native population rather than large-scale immigration. Settlers who came to the New England colonies, particularly the Puritans, arrived as couples or families, making intact family units a central aspect of the community structure there.

Also English Colonies were largely autonomous as long as they paid taxes and followed British trading laws, whereas the Spanish central government micro-managed colonization, and the appointed governors were expected to earn rewards from trade and tribute.

No comments:

Post a Comment