We have mentioned before in this space that trips to El Rancho de las Golondrinas living history museum frequently evoke (often heartfelt) personal memories in our visitors.

Although the intensity of the emotions were a bit unexpected – this human connection with material objects from the past was not. Back in Connecticut when we were clearing out Marsha’s mother’s house we donated several old kitchen items – bowls, etc. – to our local historical society thinking they could go into its annual “Attic Treasures” tag sale fundraiser. Instead they found their way into the cooking area of an historical house the organization owned and opened to the public. The artifacts were from the 1940s and 50s and thus within the lifetimes of many if not most of those who toured the building. And generated similar, albeit less fervent, reactions. (This was New England after all.)

Some housewares on display at las Golondrinas go farther back in time and yet still can cause these types of reactions. Other memory triggers are the buildings themselves, sheep, burros, locations used in movie scenes and – one that surprised us – dirt floors. “My [New Mexican] mother grew up in a house with floors just like these.” or “grandma’s house had dirt floors.” Spoken by guests younger in age than our own son.

We personally have never lived with earthen flooring. Nor did our parents, who grew up in the kind of multi-story wood/cut-stone homes common to 20th century Central Connecticut cities. As to our grandparents, born in the second half of the 19th century in Europe – well we’re just not sure.

At that time in Poland buildings of all kinds were made of timber – roofs, walls and flooring. Budapest Hungary was evolving from a medium-sized settlement to one of the largest cities in Europe, erecting apartments of brick and cut-stone up to four flights in height, and single-floor buildings of the same materials. Italian housing was commonly two levels with an external masonry stairs and wood floors covered with tiles. While in Ireland a good number of rural houses were single-room mud cabins with clay floors. So it is possible that one of our progenitors may have beat his feet in the Tipperary mud.

And what of the history of dirt floors in the New England in general?

Fodor’s Travel Guide tells us that Plimouth Plantation and Old Sturbridge Village living history museums show the “amazing contrast between the dirt-floor hovels of 1630 and the burgeoning technology of Sturbridge, in the early 1800s.” Ergo, those who came over on the Mayflower may have initially trod on earthen flooring – but not eight generations later. Meanwhile in New Mexico, which was claimed as a Spanish Colony 32 years before the Mayflower touched shore, dirt flooring was still common into the 20th century. How come?

Well for one thing – sawmills. “The first colonial sawmill [in America] was erected by the Dutch in New Amsterdam in the 1620s. The first English sawmill was built in Maine in 1623 or 1624 and the first sawmill was erected in Pennsylvania in 1662.” (engr.psu.edu) But none until the mid 19th century in New Mexico. Again, why?

Spain viewed New Mexico as an “extractive colony” caring less about building settlements and more about transferring as much wealth as possible from it back to the homeland. Supplying technology such as sawmills was not part of the business plan. Especially given the difficulties of transporting such a facility by ox-drawn carts up the 1,600 mile Camino Real – the trade route on which items from Spain traveled through Mexico City to Santa Fe. And vice-versa.

Another reason was Spain’s unwillingness to allow its northernmost New World colony to trade with anyone except itself – especially not the ever-expanding United States. New Mexico lived under that embargo from 1598 until 1821 when Mexico won its independence from Spain and with it custody of Nuevo México – which it used as its contact point for commerce with the U.S. via the Santa Fe Trail east and the Old Spanish Trail west.

It was not until 1847 that a lumber processing plant arrived in New Mexico – brought by the occupying U.S. Army to be used in the construction of Santa Fe’s Fort Marcy. It was converted into a grist mill just five years later, repurposed into a home and studio by the artist Randall Davey in 1920 and later donated to the Audubon Society of New Mexico.

Sun-dried clay bricks mixed with grass for strength, mud-mortared, and covered with additional protective layers of mud continued to be the basis for traditional New Mexican homes. And hand sawing could satisfy what demand for lumber there was. Floors were made of clay that was compressed on top of a stone foundation and sealed, usually with animal blood. (At las Golondrinas we do not “blood” the floors because of the labor involved and the amount of foot traffic.) The Spanish had brought this adobe architectural style with them to the New World having learned it from the North African Moors who ruled Spain from 711 A.D. to 1492 A.D. In New Mexico they came upon the remarkably similar Native American Pueblo structures begun as far back as 1150 A.D.

Then, on July 4, 1879 the AT&SF Railroad, and the associated businessmen from the East and their families came to Las Vegas, NM. And brought with them the eastern architectural style with which they were familiar– notably multi-story stone-cut brick and lumber Victorian homes. Plus the railroad technology to more easily transport stone-cutting, saw-milling and other technologies to the building site.

Likewise Santa Fe was becoming “Americanized.” “First, they introduced what came to be known as Territorial Style, buildings constructed of brick with straight walls and no step-backs [then added] Neoclassical, Greek Revival, Romanesque, Victorian, and Gothic elements to structures … front porches, pitched roofs, brick copings, and double-hung windows.” (lascruces.com)

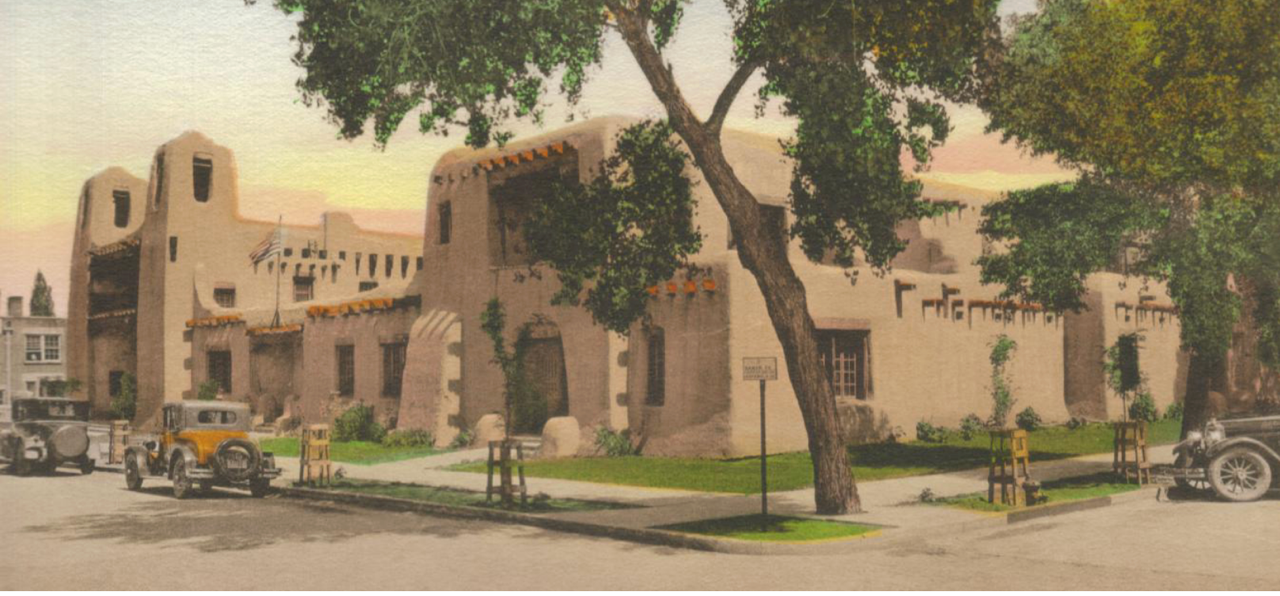

Trains brought tourists. And in the early 1900s Santa Fe’s “powers that be” realized the city’s “centuries-old tradition of Pueblo and Spanish architecture … was an asset they could employ to attract tourism and the flourishing economic benefits that accompany it.” They decreed an official style called Pueblo Revival, which “imitates traditional adobe pueblo architecture, though many newer buildings use brick and concrete instead of sun-dried mud bricks. If adobe is not used, structures are built with rounded corners and thick, canted walls to simulate it. Walls are covered with stucco and painted in earth tones.” (lascruces.com)

Dirt floors were not required. And thanks to the new availability of sawed lumber they began to be replaced by wood flooring even outside of the “historic area” to which the Pueblo Revival edict applied.

But not completely. At las Golondrinas our late 19th century Sierra Homestead area shows a family compound that would have housed a young couple with children and their elderly parents (his and hers.) Three houses show the progression of building styles from “Grandfather’s House ... with packed earthen floors [and] logs rather than adobe for the walls – essentially a log cabin covered in mud plaster; to “Grandmother’s House” with the same type of walls but a pitched roof and wooden floor of sawed lumber; to “Mora” House a large adobe home with a pitched wooden roof, covered porch and wood flooring. (las Golondrinas Guide Book) A point we mention when interpreting this section is that although more modern building materials and techniques were available Grandfather still preferred living and sleeping in his earthen floor abode after eating with the family in their more contemporary accommodations.

This practice continued well into the 20th century. As vividly recalled by so many of our Golondrinas guests triggered by the museum’s mnemonic memorabilia.