The Merriam-Webster online dictionary tells us that a cryptid is “an animal (such as Big Foot or the Loch Ness Monster) that has been claimed to exist but never proven to exist.”

This Christmas our daughter-in-law and son gifted us “Connecticut Cryptids - A Field Guide to the Weird & Wonderful Creatures of the Nutmeg State” by Patrick Scalisi. The author says he has a certificate in "Cryptic Field Observation Studies" from Nutmeg State University – an institute of higher learning with a plane of existence similar to that of the subjects of his area of study.

Despite living for over 70 years in CT we had heard of only three of the 42 documented critters. However we were not believers, so we never really sought them out. But we do enjoy a good story. And some these tales are pretty entertaining. They also can tell the reader interesting things about the culture and history of creatures’ home territories. Or at least that’s what we tell ourselves as – prompted by this new knowledge – we now begin our search for the cryptids of our present home state, New Mexico.

But first a few words about those discussed in the book.

Unfortunately none of the towns in which we have lived – Hartford, New Britain, Rocky Hill or Wethersfield (our most recent one) – can lay claim to any. There are however “unsubstantiated rumors” that the Connecticut River Serpent (“Connie”) listed as living in Cromwell, Middletown, Old Lyme, Old Saybrook and Portland may also spend time in Hartford’s Park River. A portion of that CT River tributary was buried under the city in the 1940s, which may explain why Marsha was unaware of of the large snake’s visits when she was living in that part of town.

The closest to us geographically would have been in Glastonbury, immediately across the Connecticut River from Wethersfield. The Glawackus was a mysterious creature that terrorized Glastonbury in 1939, attacking livestock and pets, “variously described as part-dog, part-bear and part-cat, but all terror!” (damnedct.com.) And the Glastonbury Pterodactyl was a prehistoric flying dinosaur that took to soaring over that town in 1958. We were never aware of them during our 40 years in Wethersfield, even though we frequently visited their home territory. However no one else seems to have seen them since their original appearances, so that could explain our ignorance of them.

The cryptid we were most familiar with was the “Nauga” – an ancient race of knee-high, rotund, short-limbed creatures that willingly shed their skins providing U.S. Rubber in Naugatuck with the raw material for their many “Naugahide” faux-leather fabrics. Until “unfortunately Naugas became a favorite target of hunters and poachers” forcing the company to establish a ranch in an undisclosed part of Wisconsin and several other secret preserves throughout the country to allow the small, docile creatures to live in peace. All financed by the Nauga Defense Fund (NDF.) At least according to the book.

Now some may scoff at our earlier comment about cryptids teaching interesting things about the culture and history of their home territories. But that idea actually does have support from some for whom studying the past is a profession. Connecticut friend P – published baseball historian, former Naugatuckian and a recipient of this missive – reports that his former home town’s historical society proudly displays the Nauga’s image on some of its official communications. Therefore it must be … somehow historic.

So with that for cover we go in search of some New Mexico’s beloved cryptids. The first two of which – Chupacabra and Thunderbird-Teratorn – may seem a bit similar to the pair that inhabited the town across the Connecticut River from us. But on steroids. We begin with the Chupacabra.

In New Mexico hummingbirds are known variously as quindes, tucusitos, picaflores or chuparosas – the last translating as “sucks roses.” An adorable image of the hardworking hoverers. But not all “chupas” are cute. Submitted for your approval is the considerably less appealing chupacabra or “goat sucker.” But cabras are not the vampirish creature’s only victims. Apparently any livestock or domestic animal can fall prey to this sometimes large, lizard-like, spiny-backed hybrid sometimes hairless canine (depending on the source). First reported in 1995 in Puerto Rico the legendary creature now ranges throughout Latin America – and New Mexico. Including Santa Fe.

The Thunderbird-Teratorn is kind of a composite cryptid. The Thunderbird is a supernatural being found in most in Native American mythology – so named because the flapping of its powerful wings sounded like thunder, and lightning shot out of its eyes. It protected humans from evil spirits and brought rain and storms, which could be good or bad. Teratorns were prehistoric birds that were the ancestors of today’s vultures and lived in New Mexico during the during the Late Oligocene and Late Pleistocene eras. They likely coexisted with early humans, at which time their identity and that of the Thunderbird became one in some cultures. Their skeletal remains indicate wingspans of as much as 20 feet or and weights of more than 100 pounds. It was assumed to be extinct. However, witnesses reported seeing the birds flying over New Mexico until the 1800s with a report of one being shot down in tombstone, AZ in 1890. Some claim the extraordinarily large birds can still be seen in the Doña Ana Mountains, outside Las Cruces, NM.

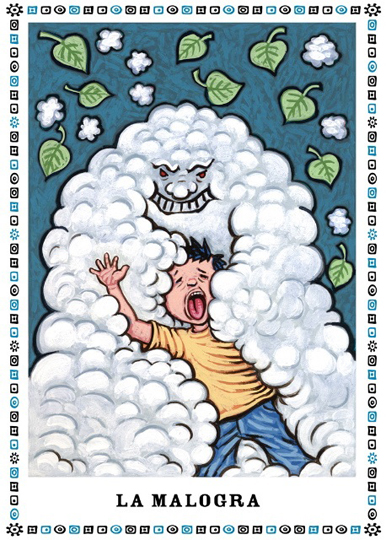

Out next creature – the “cotton cryptid” as we refer to it – is distinctly New Mexico. We looked for others with Google search. But all that we got was natural fabric clothing adorned with cutesy images of imaginary beings. La Malogra on the other hand is the real deal – “a monster formed out of cottonwood fluff, which smothers children until they can’t breathe.” (sofarfromgod.wordpress.com)

Now that may sound like not a bad way to go. But in spite of its outward appearance the smothering cloak is apparently not entirely soft and fluffy but rather a “thing that might be described as made of sharp metal and splintered wood, of limestone, gold, and brittle parchment.” (ibid) Not such a cuddly way to croak. La Malogra is said to haunt the crossroads at night in search of those traveling by themselves – especially children. According to Spanish Folklore Scholar Aurelio Espinosa it “looks like a large lock of wool, or even an entire fleece, that expands and contracts in size.” With deadly consequences for those who wander alone in the dark. A unique-in-all-the-world, 100% natural fabric cryptid.

And now for something really scary. Movie producer George Lucas introduced the world to the Skywalkers who played a significant role in galactic history of Star Wars. New Mexican novelists Tony and Anne Hillerman brought the Skinwalkers of Navajo folklore to the attention of their readers. The former – mostly good guys. The latter – not so much.

Harmful human witches who shape-shift into lethal animals at night, skinwalkers initially attain their evil powers by murdering a close relative. When the transformation is complete, the human witch inherits the speed, strength, or cunning of the animal – owl, coyote, fox, crow, or wolf. Witchcraft is an integral part of the Navajo conception of the world and their daily behavior is patterned to avoid it, prevent it, and cure it. “The general view is that skinwalkers do all sorts of terrible things --- they make people sick, they commit murders,” says Dan Benyshek, anthropologist at UNLV. But the Navajo are unwilling to share much about their evil witches because doing so might attract attention from one of them. Or even worse the interviewee themselves just might be one, looking for their next victim. So, that’s enough research for now. Perhaps forever.

The last New Mexican cryptid we will talk about today is our favorite and one whose image we see enjoy everyday at our house – the jackalope. A cross between a now extinct pygmy-deer and a species of killer-rabbit it has the short-tailed, hare’s body and spiky antlers growing out from its head. This creature has long been a part of the American West dating back to the trappers who first settled in the region in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The jackalope also appears to have a German cousin, known as the wolpertinger and a Swedish one called the skvader.

In the U.S. “jackalopes are said to be so dangerous that hunters are advised to wear stovepipes on their legs to keep from being gored.” (wikipedia.com) The creature also can imitate the human voice. “During the days of the Old West, when cowboys gathered by the campfires singing at night, jackalopes could be heard mimicking their voices or singing along, usually as a tenor.” (ibid) In spite of the rabbit’s well-documented reputation for fertility, jackalopes breed only during lightning flashes.

Some way-too-serious scientists do not believe in the mythology of the jackalope, averring instead that the creature’s horns are the result of a virus called papillomatosis, which causes certain growths to harden on the top of a rabbit’s head, resembling antlers. And they have the physical evidence to prove it. So? As comedian, former faux Presidential candidate and Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour “editorialist” Pat Paulsen would say when confronted with seemingly irrefutable facts – “picky, picky, picky.”

The jackalope image that we see each day hangs on the wall overlooking our kitchen. We purchased it several years ago from the artist, Amy Ringholz, who was delivering some of her works to a Canyon Road gallery when we happened to be there. We both liked it immediately and bought it on the spot. But we had to wait to take possession because the paint was not dry. Amy explained, perhaps with a wink, that she had created it that morning when she saw the subject posing alongside the road on her way into Santa Fe. We gladly waited for delivery having been assured of the authenticity of our purchase by its creator. (In the world of art, provenance is everything.)

Which somehow brings us back to the Naugas. As we remember it, in the 1970s UniRoyal was giving out stuffed toy Nauga dolls with purchases of their Naugahyde products – which we never did. Unfortunate. Knowing what we know now about the (crypto)historic significance of the alleged animals, we might perhaps have displayed it with the Native American sculptures above our Kiva fireplace.

But today, looking at the factual jackalope image staring undemonstratively into at our kitchen, we’re thinking that a painted portrait of one of the actual little CT cryptids would be even a better thing to have. Only the real deal though – wet paint preferred.

Text us immediately if you come across one.