(Originally written 10/21/24)

Well sadly the last hummingbird of the season has “left the building.” It has been at least three weeks since any of the tiny colibri have been seen sucking on the agastache plants outside our bedroom window during our early morning stretching routines. Or at any other time. Same for dining at the red plastic feeders. Alas, ‘til next year.

But wait… A couple of days after realizing our loss we saw one hovering at a penstemon plant in the garden of another property about ¼ mile away. Could it be that the bird just didn’t get the “time to go” memo? Were there grounds for hope? Or was it just result of one of The City Different’s climatological quirks?

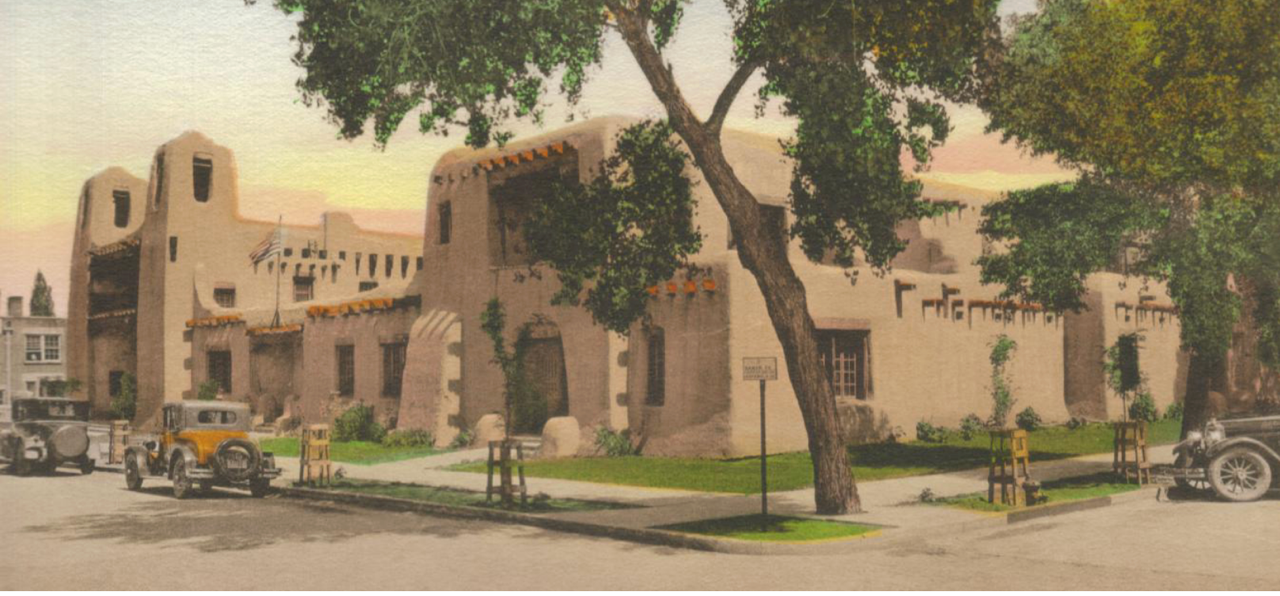

Santa Fe’s elevation averages around 7,000 feet. Out neighborhood is 7,200. The town is nestled into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains the tops of which top out around 13,000 ft.

The blog.outspire.com website says, “living at high elevation is a bit of a challenge. If you cook, it means that recipes have to be adjusted or cake batter will rise out of the pan then collapse. [Marsha took a “high-altitude cooking class” at the Community College and uses the “Pie in the Sky Successful Baking at High Altitudes” cookbook to avoid such things.]

“There is less atmosphere over our heads – less atmospheric ‘weight’ – so water boils at a lower temperature and rice or pasta needs longer cooking times. Because the air is less dense, it doesn’t retain heat, which means that we experience bigger temperature swings between sunny and shaded places, or between night and day. [Our rule of thumb for sun vs. shade is 15-20 degrees F difference.] Daytime high temperatures are on average 30 degrees F above nighttime lows.”

And then there are the Santa Fe micro-climates.

Outspire.com continues, “we had snowshoeing guests [in February] who were very dismayed to arrive and find almost no snow in town. In fact, daytime highs were in the high 50’s, we were all in shirt sleeves – [see above sun vs shade rule] and it seemed impossible to them that we would be able to have a snowshoe outing … They were amazed and delighted by the two-plus feet of snow on their mountain trail.”

After seven years out here we’re come to accept such things. We are no longer surprised to be caught in a 30-minute monsoonal rain downpour and find a totally dry street when we arrive at our home four miles away. Other similar examples abound. Mostly involving precipitation. But how “micro” are these micro-climates anyway?

Well, as blog.outspire.com points out, “two sides of a small gully in the woods may have different plants … because of the slight differences in sun exposure and moisture.” Is that what explains the color and condition of a quintet of adjacent locust trees on our street’s snow-shelf? The five showed a tree-by-tree time-lapse of leaf deterioration with the farthest from our abode beginning to drop its yellow leaves and the one closest to us still entirely green – while the three middle ones in turn showed a little yellow foliage, the next somewhat more and the penultimate one still more. Another result of “slight differences in sun exposure and moisture…”

Our main goal on the walk that brought us past the late-to-leave hummingbird was to check the copse of cottonwood trees at one end of our community’s main arroyo – “a watercourse that conducts an intermittent or ephemeral flow, providing primary drainage for an area of land of 40 acres.” (wikipedia.org) A portion of our paved walking paths parallel its banks.

Cottonwoods grow where the water is. Which is how/why when you look at the NM landscape you can tell where the rivers and streams are without being able to see the water. Our arroyo is a textbook “intermittent or ephemeral” waterway. (YTD rain is north of 13”. Woot, woot!) However over the years enough H₂O has accumulated alongside one portion of the gully to support three of these thirsty poplar trees. Because of this unseen reservoir and their unfettered access to the daily sun this tree trio is among the last of the vegetation around us to metamorphose into its autumnal yellow hue – basically the only fall color that we get out here.

The other abundant deciduous tree out here is the Aspen – most common in New Mexico at elevations of 6,500 to 10,000 feet. Which for Santa Feans means the annual drive up Hyde Park Road towards the 10,350 foot high Ski Basin to enjoy its various vista points and hiking paths, most notably the eponymous “Aspen Vista Trail.” Poorly planned road construction this year however has restricted such trips to Sundays. Nonetheless several thousand leaf-peepers are showing up at each of the allotted secular Sabbath gatherings. Normally we would be among them, however we have opted to wait ‘til next year.

We did however take part in another Aspen leaf senescence ritual. From our community we get to watch portions of the Sangre de Cristo mountains change on a daily basis from a Summer-long solid green to an amorphous yellow and green pattern as the Aspens turn amidst the non-deciduous Pines, which steadfastly maintain their healthy hue. (Sorry, no good pix. But for those who remember such things it is like watching a multi-day, slow-motion card stunt section at a college football game – e.g. this BYU tradition.)

And then there’s the chamisa.

Also known as rabbitbrush, chamisa is a hardy shrub that grows well in poor conditions such as coarse and alkaline soils, prefers full sun and requires little water. In other words, New Mexico. Hiding in plain sight with its dull gray coloration for most of the growing season chamisa proudly proclaims its presence with clusters of fragrant, butterfly-attracting golden flowers in late summer and early fall. According to the SF Botanical Garden, “this misunderstood plant is one of our area's most important pollinators, and often gets blamed for causing sneezes and sniffles. [Much like ragweed back east.] But actually, its pollen is so sticky, it doesn't go airborne! So, the next time someone sneezes and blames our friend the chamisa, kindly inform them that the cause of their nose-tickles is actually everything else that's blooming.”

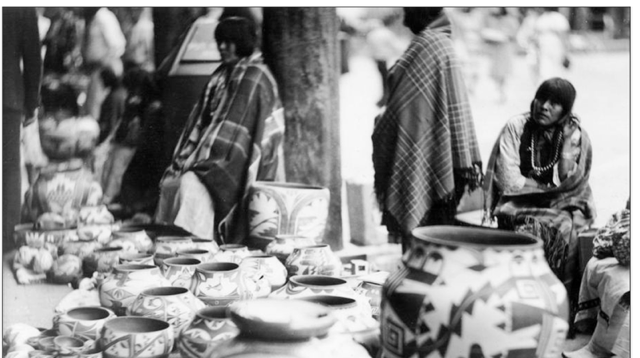

At El Rancho de las Golondrinas chamisa (“one of the oldest known dye plants in the area”) is one of the stars at our annual October Harvest Festival “creating beautiful shades of yellow” at the Dye Shed station. Its flowers and stems were used by pre-contact Navajo and Zuñi Native Americans as their primary source of yellow dye. Back in Europe the Spanish weavers’ source for that hue had been weld – a biennial plant native to that continent and Western Asia, but not the desert southwest of Nueva España. Once again “doing what they could, with what they had, where they were” the early New Mexican colonists switched to chamisa.

“The Spanish settlers carded, spun and wove wool to make rugs for the floor, blankets for the bed and horses, and clothing – including sarapes (blankets or shawls worn by men) and rebozos (shawls worn by women). These woven goods and sheep were the most important commodity exported from New Mexico … Wool was either left its natural color or prepared with natural dyes [that were] typically grown on the ranch, but brilliant blues such as indigo and rich reds using cochineal (cochinilla) were imported from Mexico over the Camino Real.” (El Rancho de las Golondrinas)

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish the color palette of Indigenous weavers (Navajo and Pueblo) was mostly brown, white, and indigo – the latter “obtained through trade and purchased in lumps.” (wikipedia.org) In the mid 1800s black, green, yellow, gray and red were added. This red was mostly raveled (untangled) yarn from other textiles with some occasional cochineal, “which often made a circuitous trade route through Spain and England on its way to the Navajo.” (wikipedia.org) For yellow the Natives used chamisa – which they also utilized for tea, medicines, food and baskets.

At Harvest Festival most of the dye-talk usually centers around cochineal and indigo – the big guns of the all-natural fabric-coloring world. But this year there was also much marveling at the profusion of chamisa and its unusually bright yellow color. Even more than was needed by that sizable statewide community of New Mexico weavers who still do it the natural way.

Climates, both micro and macro, change with the seasons. Especially true in an area with four true seasons – each creating its own ambiance marked by its own memorable features. Not all of which are repeated next time around. (During the summer of 2018 for example the open spaces in our community and other similar areas were teeming with wild cow pen daisies – never to be seen around here since at any time in any place.)

Within a month the chamisa’s yellow coloring will fade to gray – to reappear again next year, just about the time the hummingbirds depart. Or so we hope. If not we the two have paintings by local artists, which book-end this email, to remind us of what we are missing. As author Janet Fitch tells us “memory is the fourth dimension to any landscape.”